Feminist vlogger Kat Blaque kicked off the new year on Everyday Feminism with the contention it is impossible for black people to be racist. StickyDrama must disagree: Everyone can be a little bit racist sometimes–even blacks. We reached out to the influential social justice warrior for comment.

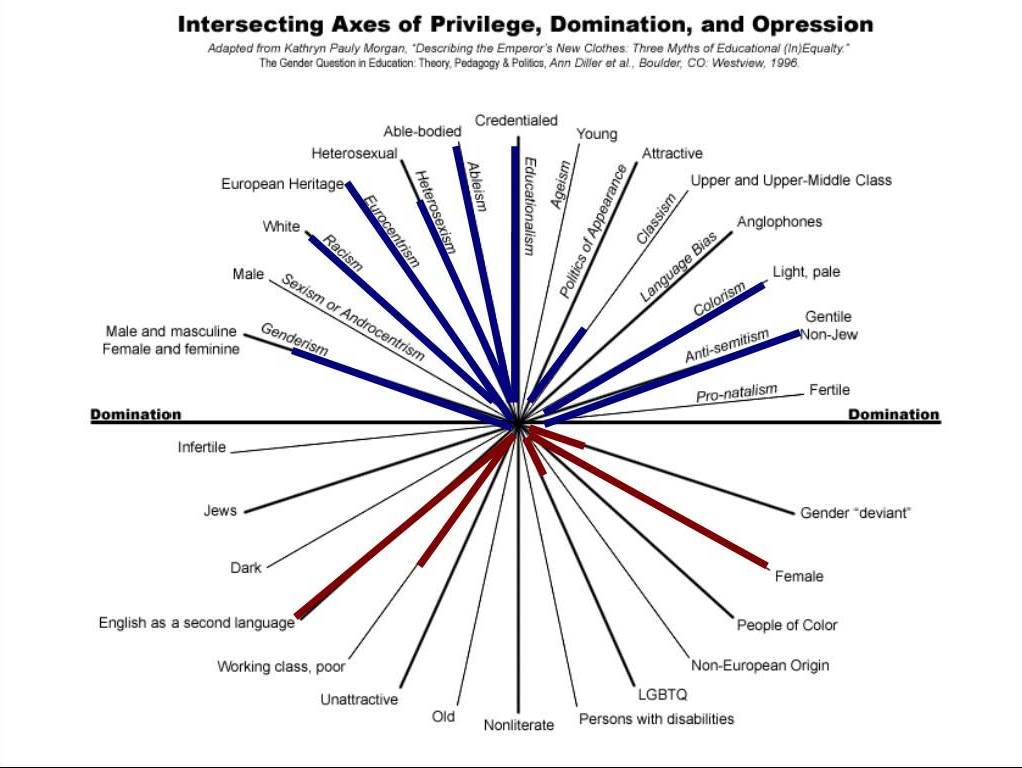

First, a little backstory: As a black trans woman, Kat Blaque is a self-proclaimed “intersectionality salad” who has become an authority on matters of race and gender. “What the hell is intersectionality,” you ask? Intersectionality is a school of feminist thought that views the interplays of domination-oppression and privilege-disadvantage in a multidimensional analysis of identity; individual identities exist at the “intersection” of lines of race, gender, class, etc. Intersectional feminists don’t tell us to check our privilege; they tell us to check all our privileges.

Black feminist Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to describe the situation of black women who faced more discrimination in the workplace than white women and black men. Its meaning has since expanded as it encroached upon and ultimately consumed “kyriarchy,” feminism’s former vogue word. How did kyriarchy lose her feminist crown to intersectionality? Vogue words come and go, but kyriarchy had several disadvantages vis-à-vis intersectionality: Kyriarchy refers to an abstract system of domination and oppression that is difficult to visualize, whereas intersectionality emphasizes concrete individuals.

But most damning of all, kyriarchy was coined by a white Christian woman, which was deeply problematic to Third Wave feminists. In a victim culture gone mad, any idea expressed by a white person is more problematic than the same idea expressed by a black person.

Anyway, Blaque espouses many, many, many SJW views, but perhaps none is more controversial than her recent doozy that black people are incapable of racism. She explained her reasoning by making a distinction between racism and prejudice:

First and foremost, I think that we need to make a distinction between racism and prejudice, right? Because I think that a lot of us – especially if we grew up in the 90s – have this view of racism where it’s always this prejudice that you have based on skin tone…. But that’s not racism. Racism is so much more than that. Racism is a system. Black people can absolutely be prejudiced. But they have not held the power in this country to actually systemically oppress a white person…. [Reverse racism is] not a thing. It’s not real. There’s no system that’s built up against white people to say, “Well, because you’re white, you can’t have access to this, this, and this, and this.”

In other words, Blaque defines racism as systemic oppression based on race rather than as isolated instances of racial hatred or prejudice, a view of racism that has been termed the “prejudice plus power” formulation. No matter how much hatred a black person may feel toward whites, no matter what awful thing a black person may do to a white person, no black person’s thoughts or deeds can constitute racism, according to the “prejudice plus power” view, because black people lack the power to take away the civil or human rights of others in society. This rationale undergirds the “Reverse Racism Isn’t Real” campaign; however, not everyone agrees with this ontological chicanery:

Far be it from StickyDrama to whitesplain, but Blaque’s argument suffers from one fatal flaw: the failure to cite any authority for the “prejudice plus power” formula. Our criticism is different than insisting that the only correct definition of racism is the one found in the Oxford English Dictionary, which was written by a bunch of evil white men. But Blaque’s failure to cite any authority whatsoever for such a controversial statement is intellectually unacceptable. Even if Blaque has an aversion to the writings of straight white cisgender men, plenty of less problematic scholars have published works propounding the “prejudice plus power” formula.

Perhaps Blaque eschews any citation because the “prejudice plus power” formula has been always been a minority view within academia, and unheard of in common usage. Sociology scholars use the “prejudice plus power” formula to describe institutional racism, not to replace the lexical definition of racism as any racial prejudice. Not even other SJWs share Blaque’s narrow definition of racism. For example, Randi Harper, the problematically white creator of the GamerGate Block Bot, adopts the Anti-Defamation League’s definition of racism, which is the same one found in the OED.

Another possibility is that the denial of one’s own potential for racism is begging the question. In other words, Third Wave feminists tend to have an obsession with labels; perhaps they’re unconsciously distancing themselves from a pejorative label, even if the shoe fits. StickyDrama has seen this sort of cognitive dissonance before, up close and personal: the man who insists that he is straight, but for one reason or another has consensual sex with other men.

For StickyDrama, voluntarily participating in gay sex makes you at least a little bit gay and exhibiting racial prejudice makes you at least a little bit racist. Moreover, the very notion that one particular race is incapable of racism strikes us as a little bit racist inasmuch as it attributes a form of moral superiority to that race. For this very reason, sociology scholar Pooja Sawrikar–who, by the way, is also an intersectionality salad–cautioned against using the reductionist “prejudice plus power” definition to the exclusion of all others. Sawrikiar states her point so brilliantly, we have to block quote her:

A definition of racism that gives disproportionate weight to power over prejudice is based on a logical flaw. It begins with the equation ‘Racism = Prejudice + Power’, but uses the historic and current inequity in social power in favour of whites to replace power with this nominal racial group; that is, ‘Power = whites’. In this way, it falsely deduces from these two premises that ‘Racism = Prejudice + whites’, or in the words of Lewis (1995), that ‘only white people can be racist’.

The statement or belief that ‘only White people can be racist’ (Lewis 1995) is itself a negative or prejudicial stereotype. While this statement or belief does not assert that every white person is racist, it does assert that only white people have the capacity to be racist because only white people have power. This is prejudicial, because it reflects a negative generalisation about a racial group (Devine 1989). (Indeed, the term prejudice is derived from the Latin prae judicium, meaning ‘pre-judgement’).

Lewis (1995) asserts that ‘there’s no such thing as reverse racism because there’s no such thing as a simple reversal of the power relationships between Whites and Blacks’. While it may be difficult to overturn entrenched discrepancies in social power in the future, given the current and historic inequity in the distribution of social power, it is untrue that racial groups other than white have no social power with which to hold whites accountable for their racism. Thus, the prejudicial assertion that only white people can be racist is an example of how people from minority ethnic groups can misuse the social power their racial group does have, albeit currently lower than their white counterparts, and demonstrate reverse racism. In this way, it repeats the very mistake it is trying to rectify – devaluing ‘the other’. It justifies the use of racism to overcome racism, thereby perpetuating its occurrence.

Yes, gentle readers, Kat Blaque is a little bit racist. And that’s OK! Because we’re all a little bit racist sometimes.

But even if we were to agree that racial prejudice alone does not constitute racism, StickyDrama can conceive of several scenarios in which blacks have the power to oppress others, depending on how we choose to define power in a given context. (Again, a citation to a specific authority would have allowed us to consider the precise meaning of “power” in Blaque’s contention.) In prison, where blacks have strength in numbers, black inmates are known to target white inmates for sexual violence. Men arguably have more power than women, and male black panther Eldridge Cleaver infamously described his raping white women as an “insurrectionary act” that “delighted” him. And, lest we forget this glorious moment, sometimes rich and powerful blacks oppress other blacks:

StickyDrama reached out to Blaque for comment, sending her a summary of the above. To our great surprise and delight, she replied:

All I will say is that if racism were as simple as someone not liking me or calling me a nigger then that would be pretty easy for me to dismiss…. Black people do not have the socio political power to oppress white people…. Saying that this is “circular reasoning” doesn’t really have any truth to it. Racism is so much more than people just not liking each other…. [I]f your focus in this conversation is your desperate need to state that black people can [hate] white people, then you’re missing the point…. I find white men are seeking to win this “argument” while [I’m] simply parroting history. And isn’t that a great example of how little these things impact white people. That they describe [my] discussion [of] racism in game terms like “race card” and want to win the “debate” and not just recognize that racial inequality exists and has a history.

Read her full, unedited response here.

Blaque still refused to cite any authority for her “prejudice plus power” viewpoint, but StickyDrama is more troubled by Blaque’s apparent distaste for dialogue. In addition to her response, Blaque wrote about our exchange on her personal blog: “To be honest, I rolled my eyes at it. I just find these sort of comments/questions to be a waste of time and energy.” Ouch! White cisgender male tears streamed down StickyDrama’s cheeks.

JK. To be honest, we rolled our eyes at our email too. StickyDrama would never dream of asking Blaque to educate us, because that’s not her job. We would have been perfectly happy simply to write that her post was a bunch of hooey, period. But we nevertheless asked for her comment because that’s what journalists are supposed to do–and bloggers are journalists. No matter how confident we are of our ability to anticipate another side’s perspective, presenting only one side of an issue is a journalistic failure.

Maybe Kat Blaque does not consider herself a journalist, even though she has reported in the Huffington Post. Maybe she prefers to think of herself as an advocate, pure and simple. Even if that were the case, her advocacy would do better to include other points of view, if only so she could rebut them.

“I really enjoy having conversations with people who disagree with me,” Blaque wrote last year, perhaps with her fingers crossed. “I find having conversations with people who just agree with me all the time to actually be quite boring. But oftentimes, if I’ve banned you from my platform, it’s not because I’m afraid of facing you. It’s that you’ve posted some really disrespectful shit that just doesn’t really belong on my page.”

StickyDrama has no doubt that Blaque had good reason to ban folks, but we suspect that her bit about enjoying conversations is dishonest. Blaque and her clique of like-minded feminists make no secret that their platform is not a place for debate; without expressly using the term, Everyday Feminism is clearly a so-called safe space where “dominant identities” are unwelcome and “dismissing the experiences of marginalized people” is not allowed. Asking the wrong questions, no matter how politely phrased, will result in a ban just as fast as will making violent threats or vulgar slurs.

Blaque makes the point that these policies do not violate free speech or impose censorship because they are not enforced by the government. Technically she is correct; however, her policies certainly lean in that dystopian direction. More alarming, such policies have a tendency to infect the minds of college students, who are rapidly becoming Orwellian fascists. When one side of a debate is so sure of its moral superiority that it will use intimidation to silence contrary views, no one is safe.

So now here we are, Kat Blaque floating on angel’s clouds in one corner, StickyDrama sinking down the stinking abyss of evil in another. Neither one of us changed our position, and we probably never will, no matter how eloquent and well-researched an argument is made. But that’s fine–StickyDrama never sought to “win this ‘argument'” with Blaque in the sense of convincing her that we were right and she was wrong. We engaged her because adversarial situations force both sides to consider and, more importantly, rebut opposing views, i.e. fleshing out their position in ways that do not occur in comfortable intellectual isolation. StickyDrama enjoyed our unsafe exchange with Kat Blaque, and we hope that she did too.